The significance of having a place to call home has been heightened in the past year. With government officials advising citizens to stay at home to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus, attention was appropriately turned to those who were visibly homeless. Individuals experiencing homelessness, however, do not simply exist in visible places such as sidewalks, alleys, parks, and emergency shelters. A portion of those who are homeless experience hidden homelessness, which occurs in private settings: on the couches of friends and family, in overcrowded apartments, in the homes of an abusive partner, or any other form of private residence where tenancy is insecure. Some studies suggest that the number of individuals and families experiencing visible homelessness is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of the larger problem.

Taking up space in the residential settings of friends and families can often put strain on interpersonal relationships. One key tactic to minimize household tension is often for those experiencing hidden homelessness to leave the temporary residence during the day, limiting their presence. Various coronavirus restrictions have made this strategy harder to deploy, potentially destabilizing what are already insecure arrangements.

This situation raises important questions: Who experiences hidden homelessness? Why are individuals experiencing hidden homelessness? And how is covid-19 impacting the experience of hidden homelessness? The answers to these questions will make clear that there is a need to ensure that all forms of homelessness are adequately addressed and eliminated.

Who experiences hidden homelessness?

There have been many attempts now to estimate the number of individuals in Canada who have experienced hidden homelessness. Data from a 2009 study suggested that 9,196 individuals in Metro Vancouver experienced hidden homelessness between January and February. A 2013 report further estimated that, nationally, for every 1 individual in a shelter there are an additional 3 individuals who are experiencing hidden homelessness (hence the visible homelessness population being just the tip of the iceberg of the larger hidden problem). More recently in 2016, a Statistics Canada report found that 8% of citizens over the age of 15 reported that they had experienced hidden homelessness at least once in their lives.

The data has consistently shown an overrepresentation of Indigenous individuals. With this, there is an interesting urban/rural overlap. With poor housing conditions and limited housing stock on many Indigenous reserves, Indigenous individuals seek out urban arrangements. However, due to discrimination and limited financial resources (both related to colonialism) it is often difficult to secure private and long-term rental housing or homeownership. This results in frequent moves between insecure urban and reserve dwellings.

The data is less clear on the gender breakdown. Statistics Canada data shows that men were slightly more likely to report having experienced hidden homelessness than women (8% versus 7%). This is despite how other reports have suggested that women are more likely to experience hidden homelessness than men. Women, to a higher degree than men, experience vulnerability when entering emergency shelters or living on public streets. Furthermore, mothers are hesitant to expose their children to the unpredictability of the multiple crises that unfold in shelters. Thus, alternative arrangements are often preferred.

Indigenous women in particular are likely to experience hidden homelessness given the intersecting oppressions they experience (i.e., colonialism, sexism, and class). The marrying-out law heightened Indigenous women’s housing precarity. This law as part of Canada’s colonial project prohibited Indigenous women from living on reserves if they pursued romantic relationships with non-Indigenous men. Even though the law was overturned in 1985, Indigenous women wishing to return to reserves faced the problem of there being highly limited housing stock on reserves. Additionally, violence disproportionately impacts Indigenous women’s relationship to housing while the lack of Indigenous centered shelters can influence the type of homelessness Indigenous women experience. Not only are women’s shelters problematically concentrated in urban areas with very few existing in close proximity to reserves but also, too often, colonial and racist attitudes continue to exist within shelters.

The Rise of Hidden Homelessness and the Decline of the Welfare State

Hidden homelessness is a coping strategy to deal with income insecurity and has become an increasing trend in recent years. In the past, social support provided by the state would prevent many from experiencing the level of income insecurity that is now considered normal. Such support existed through the provision of social housing and more appropriate social transfers. With the decline of the welfare state, responsibilities for personal and economic wellbeing were shifted off of the state and onto the individual with the expectation that they will engage in the market to meet their own needs.

In place of citizenship rights, in which the welfare state guaranteed a certain standard of living for all citizens, are norms that reinforce and exacerbate inequalities. These new norms include reduced state intervention and increased market power. The financialization of housing and social reproduction, alongside the assetization of life, mean that the markets are primarily responsible for determining life outcomes. In terms of financialization, those with low incomes are not able to afford housing, food, medication, childcare, and all of the other means required to reproduce the individual on a daily basis and children on a generational basis. This failure is blamed on personal decisions. Poor decision making, it is asserted, prevented them from getting jobs with high enough wages to qualify for certain loans (especially mortgage loans) that would enable them to acquire assets that can then be used to supplement their market incomes.

Often though, personal decisions are not the detriment the current norms present them as. These new norms that have replaced citizenship rights have made it increasingly difficult for low-income individuals and families to maintain tenancy. Instead of ensuring that all citizens have a certain standard of living, the goal instead is to ensure capital accumulation is achieved for those with greater amounts of power (i.e. banks, states, landlords), largely through low-income individuals going into debt. When attempts to secure tenancy fail, individuals are now more reliant on extended family, friends, and charities. This reliance is what has, in part, spurred high levels homelessness in general and hidden homelessness in particular.

The Conditions of Hidden Homelessness

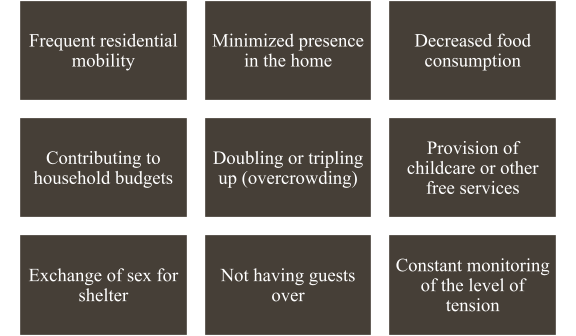

Relying on the support of others to secure housing often leads to complications. Sharing spaces can lead to unravelling of relations—even when those relations are between close kin. Those experiencing hidden homelessness deploy a number of tactics to reduce household tensions (Table 1). Typically individuals and families experiencing hidden homelessness stay with friends and family members who are only marginally better off, therefore, there are often expectations to make the arrangement mutually beneficial by exchanging space for other benefits (i.e., cleaning, childcare, contributions to the household budget, sex). Regardless of how mutually beneficial arrangements are, tensions can escalate to a point where individuals once again move to new temporary accommodations.

Table 1: Common Tactics Used by Individuals Experiencing Hidden Homelessness

As the various strategies indicate (Table 1), hidden homelessness is difficult to navigate in the best of times. In more complex times, such as what the current global pandemic presents, household tensions can be even harder to minimize. Two conflicting factors in particular can increase the difficulty of minimizing tensions. First, there are fewer places to go during the day. During periods of lockdown, drop-in centers, libraries, and coffee shops have been forced to close to the public. In non-lockdown periods these sites mean risking potential exposure to the coronavirus. Second, presence in the home is heightened given work from home and online learning arrangements. Combined, this means that not only is minimized presence in the home less feasible but also tensions are less within individual control.

One possible way to negate tensions produced by increased presence in the home is by increasing contributions to household budgets. The Canada Emergency Response Benefit potentially provided the income needed to do this. However, those without attachment to the labour market are less likely to have received this benefit. Meaning, certain populations experienced higher levels of vulnerability than others. In particular, women who exchange sex for shelter would have experienced heightened vulnerability given that they are further isolated from supports.

Oftentimes hidden homelessness is not a singular event but rather is part of a longer experience that involves a mixture of various kinds of both hidden and visible homelessness. With increased difficulty in managing the tensions there is higher likelihood of increased time spent in visibly homeless situations. Overall then, the experience of hidden homelessness during the pandemic heightens the vulnerability of individuals in multiple ways. From increased chance of exposure to covid-19 with frequent moves to further complicating interpersonal relationships that are needed to maintain some level of housing security, the current pandemic has made clear the importance of addressing all forms of homelessness equally.

The Need to Eliminate Homelessness of All Types

The Canadian government, through the Homelessness Partnering Strategy, has committed to cutting chronic homelessness in half. The problem with this, as identified by the federal Advisory Committee on Homelessness in 2016, is that the federal government does not have a solid definition of what constitutes homelessness and this has resulted in the partnered communities at times adopting the narrow definition of homelessness that does not include those who experience hidden homelessness. Hidden homelessness can still be a form of chronic homelessness. Therefore, there is a need to treat the multiple forms of homelessness with the same level of urgency. Beyond this, it is additionally necessary to better regulate the rental market and increase the wages of low-income workers and those who receive disability or social assistance to ensure that all individuals can afford a place to call home. In a country as wealthy as Canada, no one should have to experience any form of homelessness.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author, and do not reflect the views of Conversationally Speaking Magazine.

Lori Oliver

Lori Oliver is a doctoral student in the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University and a SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier Doctoral Scholar. Her research interests include gendered welfare state politics, poverty, housing/homelessness policies, and intersectional inequalities. Lori previously worked on community-based research projects with ACORN Canada, Adsum for Women & Children, and the IWK Health Centre. Her current PhD research is critically assessing gaps in social safety nets and homelessness initiatives that contribute to increasing levels of family homelessness.

Categories: Society & Culture

Leave a Reply